The Vikings were extraordinary travelers and seafarers for their time. Originating from Scandinavia during the late 8th to early 11th centuries AD, they expanded across wide areas of Europe, the North Atlantic, and beyond. Through their pioneering navigation by sea and river routes, the Vikings explored and settled in territories from Greenland and North America in the west to central Asia in the east.

Who were the Vikings?

The term “Viking” usually refers to seafaring raiders, traders and settlers originating from Scandinavia (modern day Denmark, Norway and Sweden). They spoke Old Norse, a North Germanic language ancestral to modern Nordic tongues. Beginning in the late 8th century, Vikings undertook extensive raids, conquests and trade throughout Europe, as far as North Africa, the Middle East and Russia. Over the following three centuries, their sphere of influence rapidly grew until the mid-11th century.

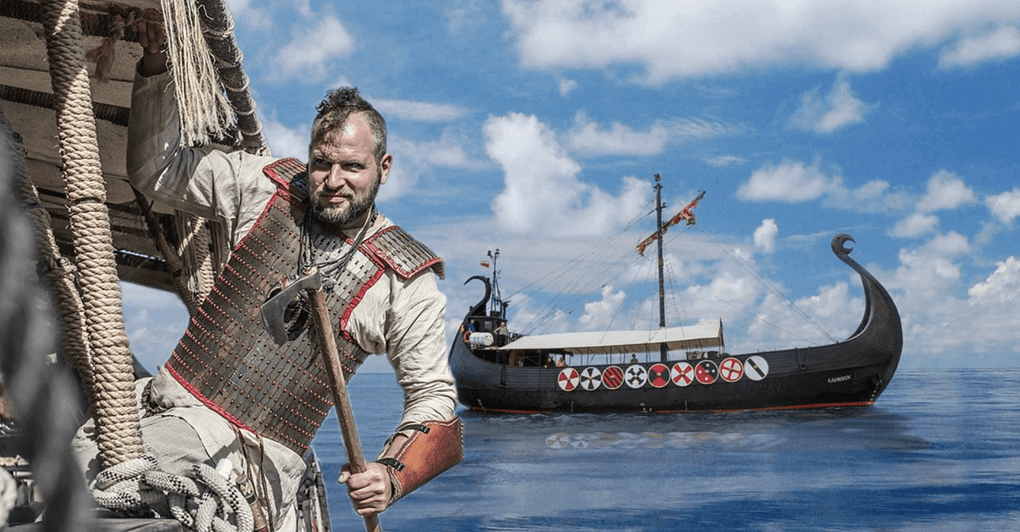

The Vikings possessed advanced sailing and shipbuilding skills which enabled them to travel great distances by sea. Their sturdy yet maneuverable longships allowed them to not only trade but also conduct raids along coasts and along navigable rivers far inland. The Vikings combined formidable combat abilities with a decentralized social structure of independent free farmers and nobles owing loyalty to local chieftains. This made them a formidable military force which became feared throughout northern and western Europe.

The Viking homeland of Scandinavia provided challenging conditions for farming which likely contributed to their overseas expansions. Some historians think population pressures or lack of agricultural lands may have prompted Vikings to seek their fortunes abroad through raiding and trade. However, others argue their homeland could sustain a much larger population and suggest economics alone did not drive the Vikings overseas.

Motivations aside, the Vikings’ travels and conquests had immense repercussions across Europe and beyond during the Middle Ages. Their expansion transformed the evolution of Normandy, the British Isles, Kievan Rus’, Eastern Europe, the Byzantine world and Islamic territories. It also brought the first permanent European settlers to Greenland, Iceland, Newfoundland and briefly further south in North America around a millennium before later colonization. Their legacy perseveres through these societies and lands they helped shape.

First Viking raids

Viking activity in western Europe commenced seemingly suddenly with devastating raids starting around 790 AD. The shocking culmination was the sack of the undefended monastery at Lindisfarne, Northumbria in 793. “Never before has such an atrocity been seen”, wrote Alcuin of York. Monks were killed or kidnapped as were valuable religious treasures plundered. Soon raids proliferated targeting coastal towns and inland rivers of the British Isles, Frisia and Frankia.

Though Norse activity in the British Isles predates the 8th century, this marked an escalation in sophistication and violence which abruptly alerted continental Europe to their seaborne menace. The Vikings’ longships, advanced maneuverability and navigational skills allowed them swift access to targets with excellent prospects for loot and ransom. Targeted were isolated monasteries and settlements with little defenses. Easily transported wealth was seized to enrich impoverished Vikings back home.

By the early 9th century Vikings began establishing bases or firths in Ireland and constructing walled fortresses throughout European coasts and navigable rivers. From these overwintering camps they launched deeper inland raids in warmer months. Their activity and range intensified dramatically during the next decades as new fleets continued arriving from Scandinavia. In stark contrast, Scandinavia itself shows little evidence of violence or population decline during this turbulent epoch.

Landnám – Settlement of Iceland

Simultaneous to raiding abroad, Vikings began colonizing less densely inhabited areas. Around 870 the Norwegian Viking Ingólfr Arnarson became Iceland’s first permanent settler, initiating the Landnám or Age of Settlement. Much of Iceland’s early colonization traced to Norwegian Vikings escaping tyrannical rule of Harald Fairhair, first king of a united Norway. By 930 Iceland contained an estimated 18,000 settlers according to Landnámabók. Many colonists brought servants and thralls (bond servants) with them.

Iceland appealed for its close proximity to Norwegian homelands and open farmlands suitable for pastoralism. Its coastline abounded in seal and bird hunting. Viking newcomers were able to acquire great tracts of land with the island’s sparse populations of Irish-Norse hermits and an estimated 2,000–3,000 Norse slaves who had fled Ireland for safety. Scandinavian languages and culture came to dominate Iceland within two centuries. Due to its isolation and environment Iceland remained the best example of Viking culture into the modern era.

Raiding and early settlements in Britain and Ireland

Meanwhile heavy Viking raiding impacted the British Isles starting in the late 8th century. Viking fleets often wintered in Ireland establishing bases for further campaigns. In 802 the first recorded raid hit Munster in south Ireland. By 830 raiding bands grew to large armies which sacked dozens of Irish monasteries and overwintered for security inland. They grew adept at traversing watersheds by portaging boats over waters dividing one river system from another. This facilitated deeper incursions on new missions in subsequent years.

Beginning in 840 the Vikings began constructing more permanent fortified bases called longphorts surrounded by earthen ramparts. Dublin emerged as the foremost Norse trading centre in Ireland established in 841. Others included Annagassan, Limerick, Waterford, Wexford and Cork. Many developed into permanent towns and cities. Dublin became a powerful kingdom in its own right, ruled by Norse-Gaelic kings. The term “Dublin Vikings” arose as they had become distinctive.

In 865 a huge Great Heathen Army landed in East Anglia under the leadership of Halfdan Ragnarsson and Ivar the Boneless. More reinforcements arrived in 872 led by Bagsecg, Oscytel and some Irish allies. The combined army overwhelmed Anglo-Saxon resistance and partitioned England into the Danelaw. York became a hub of increased Norse control in northern England until 954. During this period Norse armies also raided parts of Wales and Scotland. In 899 more Scandinavians arrived to reinforce their positions.

The Viking force fractured after 876 into fighting between Guthrum and Haesten against Alfred the Great of Wessex and forces of the Welsh, Scots and Mercians. Alfred emerged victorious after securing the Treaty of Wedmore in 878 to allocate territories on either side of the Thames. Yet sporadic Viking incursions and new leaders like Hastein continued. In 991 the warlord Olaf Tryggvason sacked London and ravaged the Thames before retiring to Normandy.

Invasions under Thorkell the Tall and Cnut the Great who secured the English throne from 1016 after victory over King Edmund II and Ethelred II’s line. Angles and Danes continued battling for supremacy until the Norman conquest of England in 1066 quelled Viking activity. Meanwhile, Vikings became absorbed by intermarriage and cultural blending into the Anglo-Saxon population over generations. Yet Norse traits endured in speech, culture and ancestry today.

Raids and mixed success in Frankia

Mainland Frankish territories like Frisia and Saxony lay defenceless and exposed to Viking hit-and-run raids from the late 8th century. Lacking coordinated naval forces the Carolingian Franks responded ineffectively paying tribute known as Danegeld to buy off raiders. Paris suffered heavy attacks in 845 and 856/7. Vikings repeatedly sacked Dorestad, an important trading centre near the coast. The inability of Louis the Pious or his successors to prevent these penetrations forced treaties with leaders like Rorik of Dorestad and Godfrid, Duke of Frisia, to establish control over raiding bands.

Yet their authority proved temporary with no means to resist the broader Viking threat. Scandinavian adventurers continued terrorising the Frisian coast and lower Rhine, plundering deep inland along other major rivers before retiring to safe strongholds like Asselt. After 882 Charles the Fat elevated Godfrid of Frisia duke over the region itself, hoping to pacify the region. Meanwhile Vikings maintained major bases even further southeast around the mouth of the Loire and Gironde estuary.

Nonetheless the West Frankish kings managed a few notable successes. In 857 Charles the Bald retook Somme River forts and burned the Viking base at Péronne. 921 saw Robert of Neustria defeat Norsemen besieging Chartres before driving them back to their Loire fortresses. William Longsword secured Rouen in 911 for the Vikings in return for conversion and baptism of Rollo, founding the Duchy of Normandy. Normandy served as a Frankish bulwark against further Viking incursions.

The Vikings continued raiding deep into Germany via Rhine, Elbe and Weser rivers well into the 10th century. They threatened Hamburg-Bremen repeatedly and sacked Bergen at the mouth of the Weser. Constant harassment by Vikings drained the Empire’s resources through payment of protection money to buy them off. Unlike Britain, only isolated Norse settlements emerged though Frisia around the mouths of rivers, protected by local leaders.

Italy and Muslim lands

Individual Vikings also raided further afield down in Italy, North Africa and as far east as the Caspian Sea. In 810 the Norse sheltered at Dorestad base joined Godfrid in looting Campania and sacking Spoleto and Fermo. 813 saw an even larger Viking fleet ravaging Sicily and N Africa. 846 some 280 boats raided and plundered Ireland, Scotland, Wales, then raided along northern and central Spain before taking Cádiz and Seville in Al-Andalus.

Later Norse mixed with Lombards in Italy. Eric Bloodaxe held rule of York for periods before battling his brother Haakon for Norway. His sons held land in Apulia granted by German emperors. Hastein raided Italy and Al-Andalus in the 860s before accepting baptism from Charles the Bald. Ahmad ibn Rustah described Rus’ Varangians establishing in “Mikligard” (Constantinople) around 859, later serving as the emperor’s personal guards. Despite periods of contact there seems to have been no Norse political settlements in Italy or Muslim lands.[1]

Eastern Europe

To the east Norse went for slaves and silver in what became Russia. At first these Norse arrived from within Scandinavia predominantly as warriors, colonists and traders rather than raiders. The Varangians ventured the Dnieper River direction to reach lands further east. Their domination of trade routes between the Baltic and Byzantium and control over its southern stretch in modern Russia around Ladoga and Staraya Ladoga opened up new trading horizons. Large numbers of Norse migrants may have headed down river by boat to the Black Sea before some wintering in Constantinople. Arabic sources first describe Rus’ merchants arriving in Baghdad around 839-842 AD to engage in slave trade and exports such as furs, honey, and tusks.

Expansion to the east brought agricultural colonization as well as trading and adventuring spheres of influence under early Norse leaders like Rurik, Oleg of Novgorod and first Rus’ rulers, influencing the political and ethnic map of Eastern Europe. The Norse left cultural and linguistic imprints from Lake Ladoga to Kiev, central Russia and down the Volga into the lands of the Volga Bulghars. They introduced Old Norse dialect words which persist linguistically to this day.

Legacy

Many aspects of contemporary European and North American societies today stand as legacies of those Scandinavian maritime settlers, traders, warriors and colonists of the Viking era and their world-spanning voyages and interactions. Their impacts ranged from geopolitics to genetics, language, mythology, literature and seafaring. In some cases, their long-term influences and migrations created new fusion peoples such as the Normans, Rus’ and Norse Gaels.

See also impacts like expansion of Christendom in Northern Europe, introduction of medieval Scandinavian placenames and loanwords, shifts in political and economic power in Britain and Europe due to Norse settlement, enduring Norse ethnic genetic strata in settled areas. Other legacies include advances in ship design, navigation, trade networks and colonization practiced by Scandinavian peoples. Together with Crusaders, Templars and Reconquista warriors they helped reintroduce European contact with the broader world once again.

The Viking movement of expansion reflected a unique period in history when Norse seafaring mastery and daring along with technological and navigational skills coincided with momentary weaknesses in surrounding territories. This enabled unprecedented Scandinavian mobility which permanently transformed Northern European societies from Brittany to Novgorod and Greenland to North America. Over three centuries they proved fearless and successful explorers, traders and colonizers. Their influence grew immense across Vínland, Garðaríki, the British Isles to Normandy – and from Ireland to the Holy Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, and further across the Caspian.

Source:

- https://www.history.com/topics/exploration/vikings-history

- https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-viking-age/expeditions-and-raids/how-did-the-vikings-travel-around-in-the-world/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viking_expansion

- https://www.thecollector.com/where-did-the-vikings-travel/

- https://www.lifeinnorway.net/viking-travel-guide/https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vikings

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zvqnnrd

- https://www.worldhistory.org/image/14067/global-extent-of-viking-exploration/

- https://sciencenordic.com/archaeology-denmark-history/see-where-the-vikings-travelled/1419546

- https://www.historyhit.com/how-far-did-the-vikings-travels-take-them/