While Vikings and Celts originated from different parts of Europe and had distinct cultures and beliefs, there were also some overlapping aspects between their civilizations, especially in the symbolism and motifs they used in their art and crafts. Many Vikings and Celtic designs incorporated intricate swirling patterns and interconnected knots that reflected their cosmologies of eternal cycles and flows. In this article, we will explore some of the main symbolic forms that were shared between Vikings and Celts or showed influence between their artistic traditions.

Origins and Spread of Knotwork Designs

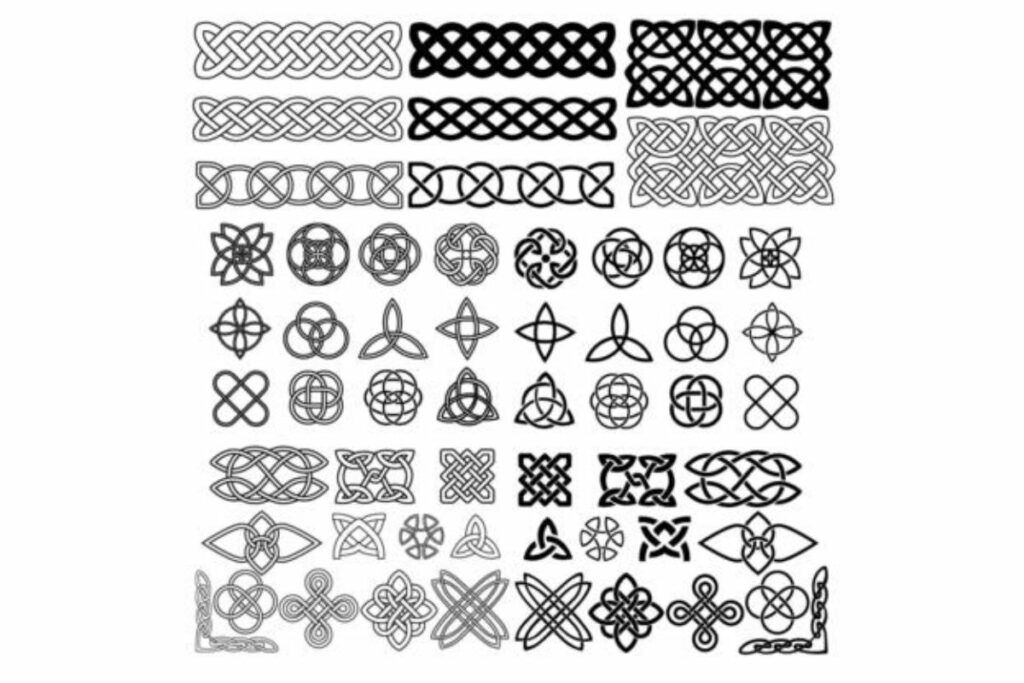

One of the most signature artistic styles found in both Viking and Celtic artifacts is known as knotwork – designs comprised of complex interlacing or interwoven linear elements without a beginning or end. Though the precise origins of this motif are unclear, most scholars agree that it emerged first in metalwork and mosaic designs from the late Roman Empire between the 2nd-4th centuries AD. Elements of knotwork designs are seen in mosaics, textiles, bronzework, and other decorative arts from this period.

From there, the motif seems to have spread into Scandinavian art from the Germanic peoples the Romans had contact with. By the Germanic Migration Period in the 4th-6th centuries AD, complex knotwork patterns adorned many artifacts of the time, like the 3rd century Gothic gold bracteates. The Norse adapted this style into their own idiom, developing intricate forms known as Urnes, Ringerike, and Mammen styles that decorated wood, stone, and metal objects from the Viking Age.

Meanwhile, the intricate knot motifs also took hold in Celtic art from around the 6th century onward in Ireland and Britain. Manuscripts like the 8th century Book of Kells are renowned for their virtuosic interlaced designs in illuminated letters and margins. Knotwork patterns also graced metalwork, woodwork, and stone during this Irish Golden Age. The interconnections show the symbolism likely spread from Roman roots into both Viking and Celtic cultures independently through exposure and artistic exchange over centuries.

Symbolism of Eternal Flows in Knotwork

So while knotwork first emerged from Roman precedents, Vikings and Celts each developed it profoundly in their own mediums and imbued it with indigenous meanings. The infinite, non-beginning nature of the swirling linear patterns held symbolic resonance for both cultures.

>>> Nordic Rune for Friendship: Meaning, Symbols, and Viking Tattoo Ideas

For the Norse, they represented the endless flows of fate, destiny, and cycles of time represented by forces like the Norns. No thread within their knots was truly first or last – like how all lives were woven into the greater web of Wyrd. Celts saw similar significance in knotwork depicting eternal natural and supernatural cycles without clear starting points or endings.

Both groups may have been influenced by observations of continuous natural phenomena like river flows, tree growth rings, or serpentine coastal inlets. The knot designs reflected their spiritual understanding of an inherently woven, borderless cosmos. Their recursive forms suggested profound connections between all things in an infinitely unfolding multiverse.

Interlaced animals, spirals, and geometric patterns on carved stones, shields, and manuscript pages in Viking and Celtic lands demonstrated the intrinsic linkages between all levels of their mythological worlds from the gods to humanity to the surrounding natural order. Over centuries, their styles diverged yet retained this symbolic significance of eternal interconnectedness.

The Triskel and Triskele Motif

Another iconic form that was independently adopted yet similarly meaningful for both Vikings and Celts was the triskele or triskelion – a motif of three interlocked spirals or bent legs. Variations occurred amongst Norse and Gaelic carvings, metalwork, and illuminated manuscripts from the 6th century onwards.

For the Celts, it had associations with cosmic balance, sacred geometry, rotational cycles like the seasons, and perhaps hinted at concepts like the ancient and ecumenical Celtic tripartite division of lands into sovereign realms. However, they too saw it as representing eternal recurring motions and the all-connecting flow between realms.

Vikings adopted triskelion artwork in a form known as valknut triangles on memorial stones for prominent leaders. Their symbolism likely tied to Odin, war, fate and the transitions between worlds. Overall, both groups seem to have seen three-legged designs as subtle reflections of nature’s infinite feedback loops and their own mythological principles of perpetual change and connectivity.

More: The Connection Between Viking and Celtic Symbols

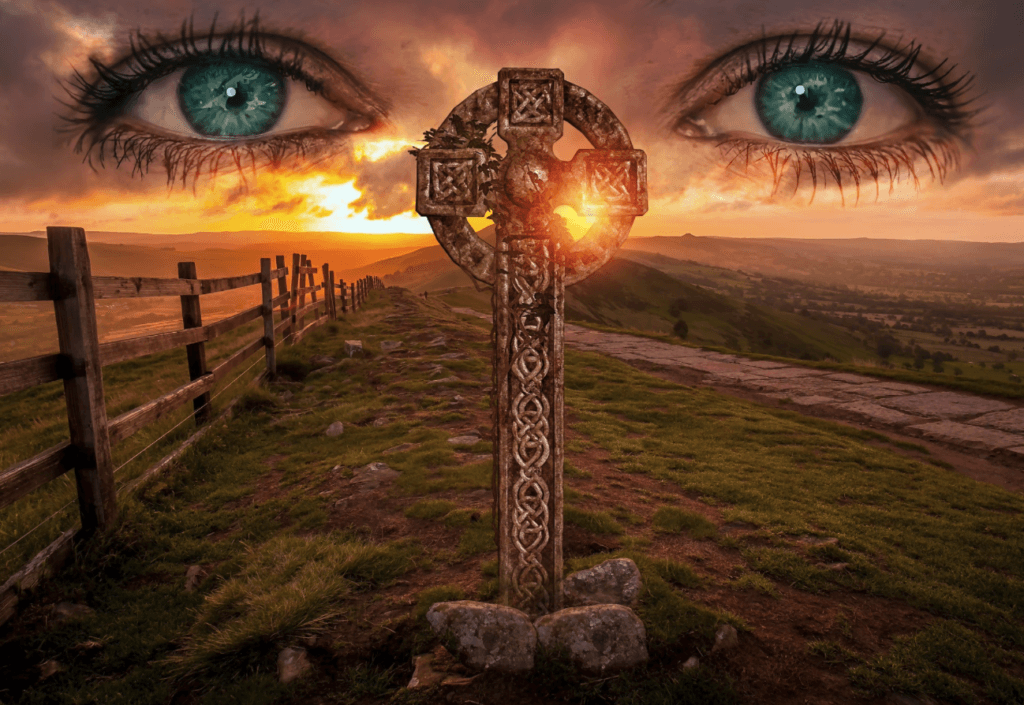

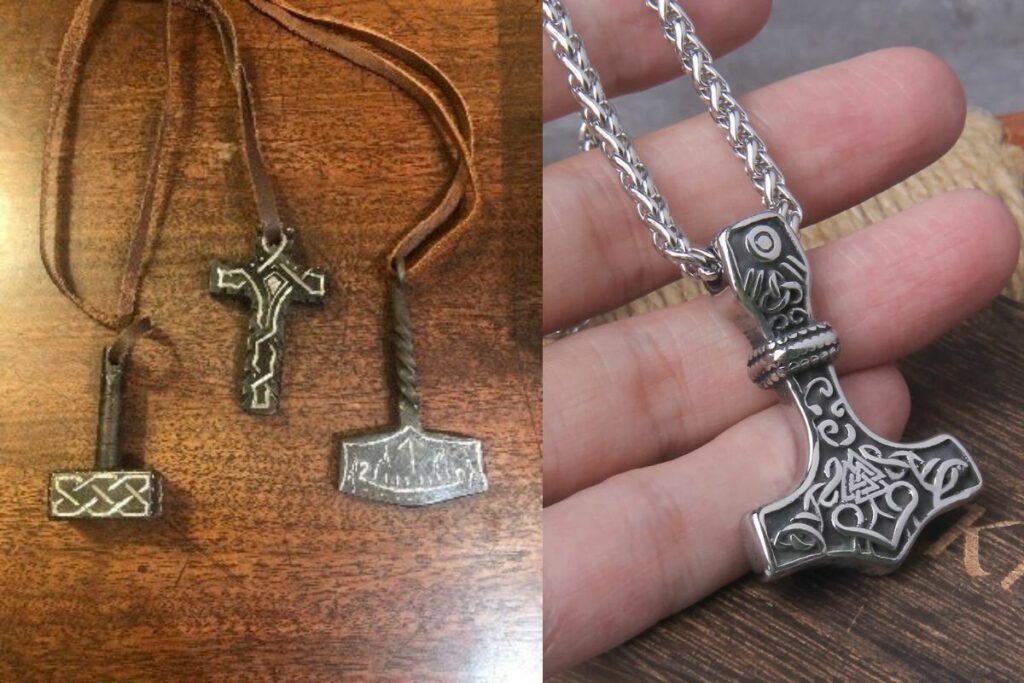

Celtic Crosses and the Viking Symbol of Mjölnir

The Celtic Christian cross developed from the 4th century in Ireland and Britain as these lands converted. Its decentralized and linear structure echoe’d older Bronze Age symbolism and accommodated pagan accretions over generations. By the Viking Age, elaborately carved high crosses already dotted the landscape and signified concepts of ancestral continuity, territorial claims and religious life for Gaelic communities.

Intriguingly, Scandinavian stone carvings from the 9th-11th centuries occasionally featured a simple cross shape too. While these held deep Christian meaning for the Irish, for Vikings they likely held more generic associations with guidance, protection or transition – taking on the properties of objects they came into contact with abroad. Their most potent and ubiquitous sacred symbol remained the hammer of Thor – Mjölnir – which protected travelers, connected the mortal and divine realms, and represented masculine strength, lightning storms and the violent yet purifying forces of nature so integral to Norse cosmology.

More: Norse Rune for Thor: The Power and Meaning of the Thurisaz Rune

So in summary, while crosses became a predominant symbol for Christianized Gaelic communities, Mjölnir amulets and pendants fulfilled a similar multifaceted role in Viking pagan religion and identity. Both motifs incorporated layers of layered meanings from their surrounding ancestral traditions and represented key aspects these groups saw as essential for safekeeping life’s passages.

Shared Myths and Gods

Additionally, Vikings and Celts incorporated some shared mythological figures into their pantheons that demonstrate points of convergence in their belief systems due to proximity and interaction over many centuries.

One such example was the figure of the smith-god Gobann, Goibniu or Gofannon amongst Irish and British Celts who was skilled in metalworking, healing and prophecy. He arguably shares attributes with the Norse god Völundr – a clever supernaturally gifted craftsman who features in both Norse and Anglo-Saxon tales. Both inhabited the mythic spaces between the natural and unnatural worlds.

Another parallel seen was between the war focused Irish goddess Morrígan and the valkyries of Norse legends who presided over battles and determined fates of heroes. Then characters like Cernunnos, a horned animal spirit associated with fertility in Insular Celtic religion, found semblances in Norse forest and animal gods like Ukko, Norvi or Týr.

While distortions likely occurred as myths crossed linguistic and cultural boundaries, these comparative figures demonstrate the sharing or influencing of certain supernatural archetypes between the belief systems due to their proximity and exchanges from antiquity onwards in Britain and Ireland. Both cultures incorporated analogous spiritual beings who navigated realities in between established realms or centered around pivotal roles in tribal societies.

Legacy in Later Folk Practices

In subsequent centuries as Scandinavian settlers fully integrated into Gaelic communities while native traditions slowly transformed under Christian influences, echoes of older symbolic interactions remained visible in emerging folk customs.

Knotwork style continued to feature prominently in traditional clothes, baskets and other crafts from the British Isles to this day. Charms like the Celtic Vesica Piscis and Norse Vegvísir compass rose gained new layers of significance protecting travelers in the Christian era too.

Folkloric beings like the Scottish Brollachan hobgoblin or Manx Claaghyn Isle of Man seem to blend attributes of Norse trolls, elves or household spirits with strands of older nature-aligned Celtic idols. Even seasonal rituals and festivals integrated aspects of both ancestral religious spheres. Yule, for one, incorporated feasting, gift-giving and spiritual protections drawn from Yuletide and Winter Solstice traditions in Scandinavia and northern Europe.

Therefore while organized religions and politico-cultural identities diverged, lasting undercurrents of symbolism, belief and mythological figures mingled in the lived folk cultures that emanated from the northern regions where Vikings and Gaels extensively co-inhabited and engaged in cultural exchanges for over half a millennium. Their artistic motifs and associated cosmologies naturally syncretized to some degree, leaving imprints discernible even in later traditional lifeways.