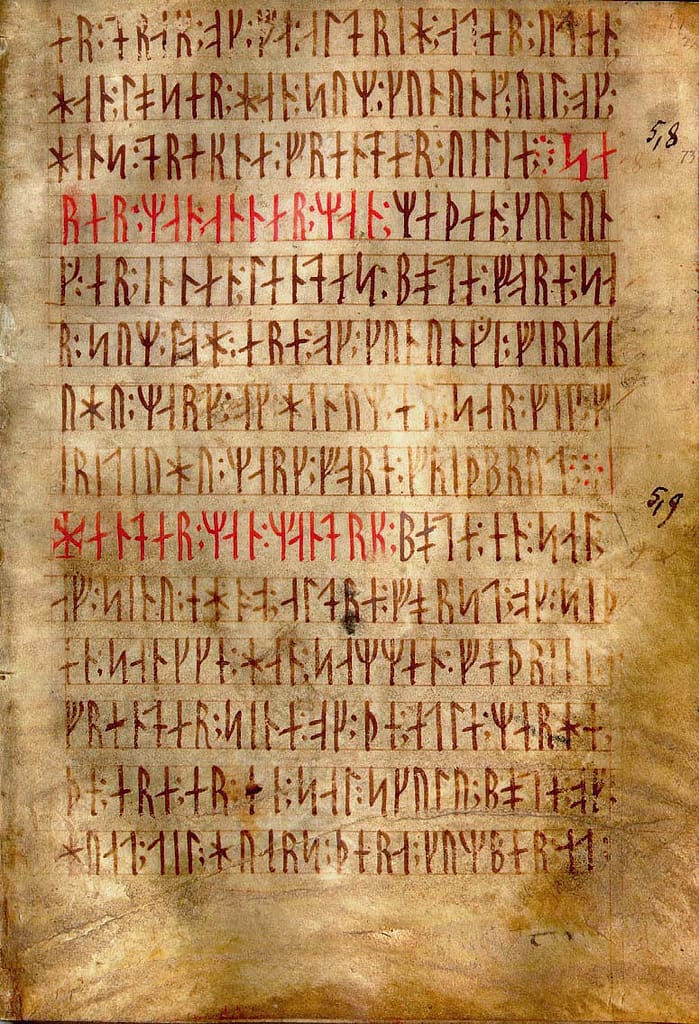

The Runic alphabet was a writing system used mainly by Germanic pagan tribes from the 1st century CE to the 17th century CE, particularly by the pagan peoples of Scandinavia known as the Vikings. As the Vikings expanded their territories throughout Europe between the 8th-11th centuries, their Runic alphabet was brought over and influenced other writing systems during that era. This article aims to provide an overview of the origins, evolution, and usage of the Runic alphabet by the Vikings based on information from Wikipedia sources.

Origins and Development

While the exact origins of the Runic alphabet are still uncertain, most scholars agree that the elder Futhark alphabet developed among Germanic tribes no later than the 2nd century CE, deriving from the Old Italic alphabetic script of the Roman Republic. By the 4th century, the 24-character elder Futhark had become established as a common Germanic writing system in Scandinavia and northern Germany. The alphabet was written and read from left to right in equal horizontal lines known as “futhark rows”.

During the 5th-8th centuries, the Runic alphabet evolved into two regional varieties – the elder Futhark in Scandinavia developed into the younger Futhark with only 16 characters by the 8th century. Meanwhile in England, the futhorc alphabet emerged with an expanded set of 33 characters to represent the unique sounds of Old English. The changes reflected phonetic reductions and mergers that had occurred in the languages.

Usage by the Vikings

As the Viking Age began in the late 8th century, the younger Futhark was the primary writing system of the Norse people and remained in common use by ordinary Norse/Vikings throughout the Viking expansion period. Runes were used for everyday purposes like divination, magic, labelling of goods, and gravestones for memorial inscriptions. It was an important mechanism for communicating over long distances in the far-flung Viking world.

Some notable uses of runes by the Vikings include:

- Over 100 surviving Viking runestones erected in Scandinavia, most dating between the 9th-11th centuries to commemorate the dead. The longest surviving runic text comes from the Rök Stone dating to the early 9th century.

- Younger Futhark inscriptions found on artifacts like the Gotland picture stones, Thor’s hammer pendants, and the Kylver Stone reflecting Norse pagan beliefs.

- Runes used for trade and communication by Viking settlers in places colonized, such as the bind runes found on the Jelling Stones constructed in Denmark in the 10th century.

- Elder Futhark inscriptions found in Viking settlements like 16 characters found on a comb discovered in Birka, Sweden demonstrating that the elder form continued in limited use.

| Rune Official Unicode Consortium code chart: Runic Version 13.0 |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+16Ax | ᚠ | ᚡ | ᚢ | ᚣ | ᚤ | ᚥ | ᚦ | ᚧ | ᚨ | ᚩ | ᚪ | ᚫ | ᚬ | ᚭ | ᚮ | ᚯ |

| U+16Bx | ᚰ | ᚱ | ᚲ | ᚳ | ᚴ | ᚵ | ᚶ | ᚷ | ᚸ | ᚹ | ᚺ | ᚻ | ᚼ | ᚽ | ᚾ | ᚿ |

| U+16Cx | ᛀ | ᛁ | ᛂ | ᛃ | ᛄ | ᛅ | ᛆ | ᛇ | ᛈ | ᛉ | ᛊ | ᛋ | ᛌ | ᛍ | ᛎ | ᛏ |

| U+16Dx | ᛐ | ᛑ | ᛒ | ᛓ | ᛔ | ᛕ | ᛖ | ᛗ | ᛘ | ᛙ | ᛚ | ᛛ | ᛜ | ᛝ | ᛞ | ᛟ |

| U+16Ex | ᛠ | ᛡ | ᛢ | ᛣ | ᛤ | ᛥ | ᛦ | ᛧ | ᛨ | ᛩ | ᛪ | ᛫ | ᛬ | ᛭ | ᛮ | ᛯ |

| U+16Fx | ᛰ | ᛱ | ᛲ | ᛳ | ᛴ | ᛵ | ᛶ | ᛷ | ᛸ | |||||||

| Old Italian Official Unicode Consortium code chart: Old Italic Version 13.0 |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1030x | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌈 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌎 | 𐌏 |

| U+1031x | 𐌐 | 𐌑 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 | 𐌘 | 𐌙 | 𐌚 | 𐌛 | 𐌜 | 𐌝 | 𐌞 | 𐌟 |

| U+1032x | 𐌠 | 𐌡 | 𐌢 | 𐌣 | 𐌭 | 𐌮 | 𐌯 | |||||||||

Interpretation and literacy

While the Vikings did not have a large literate, educated class like medieval Europe, they did value literacy to some extent. Multiple runic alphabets indicate the script was adaptable to various regional languages. Though difficult, runes could express most sounds of Old Norse. Literacy was a desirable skill for chieftains, traders, artisans as indicated by runic tags on tools, weapons, jewelry. Clerics may have had more advanced literacy to use for magical/religious texts. However, most Norse people likely achieved basic “operational literacy” to interpret everyday inscriptions and messages. Overall, the runic script played an important role in the identity and communications of Viking Norse pagans for over 600 years.

Decline and legacy

For Norse and other non-Christian pagans, the use of runes likely served religious and ethnic purposes as well as practical ones. However, following the Christianization of Scandinavia between the 11th-13th centuries, the use of runes gradually declined as the Latin alphabet became the standardized script of administration and church texts.

While falling out of common use, runes continued to be used for magical/divinatory purposes especially among peasants in Scandinavia. Some isolated examples from as late as the 17th century exist. The legacy of this writing system can still be seen in modern English, Danish, Norwegian and Icelandic languages where a handful of characters derived from runes survive today like p, ð (eth), x. The fascination for Runes and Norse history continues today symbolized by their use in popular culture on everything from books and video games to tattoos, museums and living history reenactments. Overall, the Viking runic alphabet made significant contributions to communication systems and cultural heritage of Northern Europe during the Medieval period.